Discover the city’s local history! A simple place to start is by visiting one of the more than 150 parks comprising our Milwaukee’s Emerald Necklace.

Milwaukee’s extensive history chronicles cultural connections from all over the world: From the First Nations who followed wild rice and game along the local marshy riverbanks; to the French fur-traders who arrived by boat along the Great Lakes, establishing both a port and trading post; to the Polish, Irish, Black, Italian, German, Latino, and Hmong immigrants-–among others–-who over centuries migrated to Milwaukee for a variety of respective reasons.

Spending Time with Nature

Current research shows walking and talking enhances our mental creativity. Although modern science is only beginning to catch on, this secret was known long ago. Many well-known philosophers are famous for walking while working outdoors. Plato’s school was outside, in a grove of trees called Akadēmía. Socrates was known to stroll and philosophize. Aristotle taught his classes while he walked up and down the walkways of the Lyceum.

The Stoics walked and talked on outdoor porches filled with beautiful artwork. The Roman Stoic Seneca told his followers, “We should take wandering outdoor walks so that the mind might be nourished and refreshed by the open air and deep breathing.”

The brain is always active. Even when standing motionless and doing what we think is nothing, our brain is hard at work.

While standing still, billions of neurons in our mind are firing. It therefore stands to reason much more is happening to our bodies and our brains when we walk.

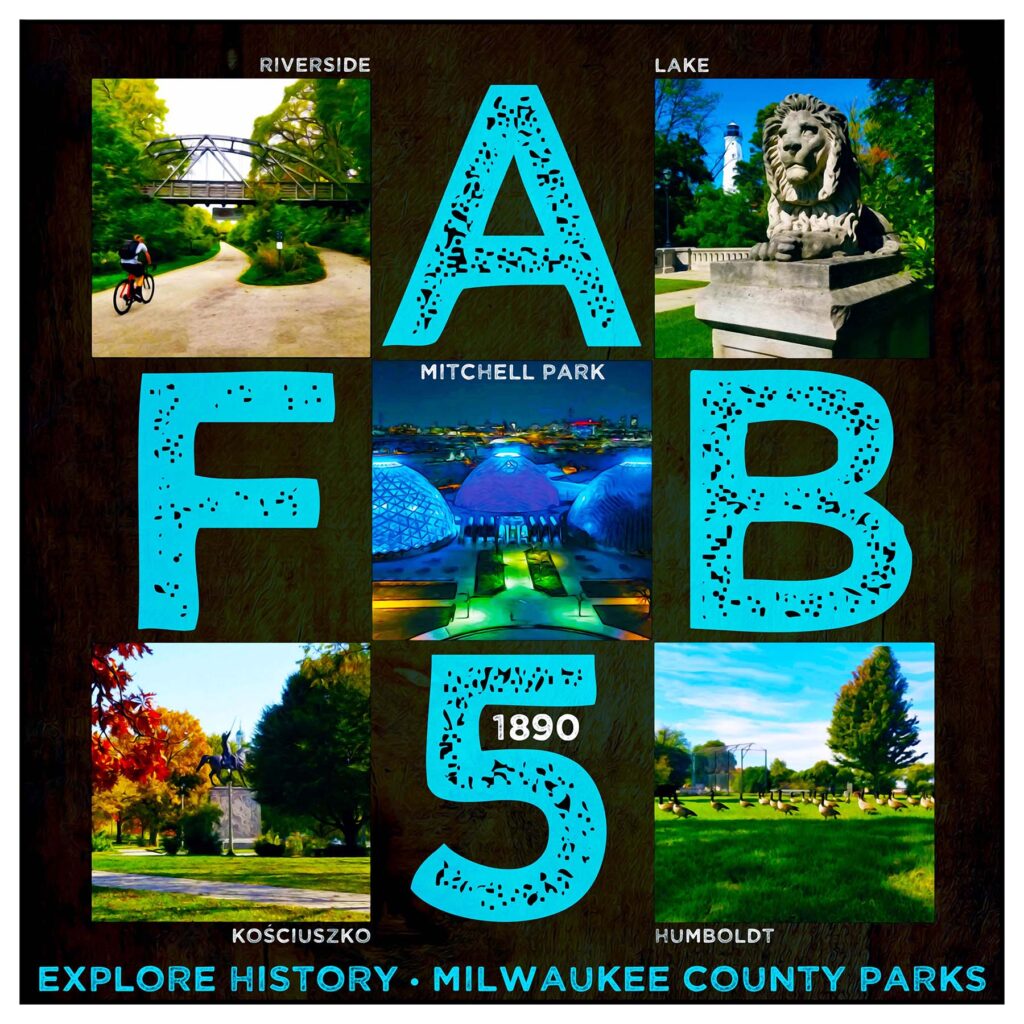

Part of Milwaukee’s Emerald Necklace.

What is Milwaukee’s Emerald Necklace?

Milwaukee’s Emerald Necklace is the term coined to describe the city’s extensive public park and parkway system. While beer has played a crucial role in shaping the city’s culture, it might be surprising to discover it also played a crucial role in shaping the city’s public park system as well.

Park locations and designs can be traced back to the rise of an industrial city. Once known as the “Machine Shop of the World,” a large percentage of Milwaukee’s early immigrant workforce at one time labored away in its production plants. The city’s many public green spaces evolved within these historical, social, and political roots.

Beginning in the early 1840s, the city’s brewing industry formed and rapidly grew from inception. European immigrants were looking for the flavor of home. They brought both a local market for traditional beers and the skills needed to produce them.

Although Milwaukee is best known for German beer barons, it was actually a team of Welsh immigrants who established the city’s first brewery in 1840.

The “Milwaukee Brewery,” later named the Lake Brewery, found its roots near the North Pier at the foot of E Clybourn Street.

This location is not far from where Discovery World now stands. Because of its proximity to the lake’s main pier, E Clybourn Street (then named Huron Street) once served as Milwaukee’s busiest thoroughfare.

Soon after, a man named Herman Reutelschöfer established Milwaukee’s first German brewery just south of downtown. He became known for his German lagers, which would soon become the city’s standard. Early Milwaukee saw the creation of approximately thirty-five more bottle houses over the next two decades. Most were founded by German immigrants.

German brewery workers had a distinct craving for both brew and the urban leisure they had become accustom to back home. In response, Milwaukee brewers began showing interest in creating Bavarian-style outdoor environments for their employees. Unlike other outdoor spaces serving alcohol, urban Biergartens surrounded patrons with water, trees, and other forms of greenery. Springing up all around the city, as time went by, the beer gardens also marked the beginning of an extensive public park system.

Seeing the success of local beer gardens, the political will for outdoor green space quickly grew. Leaders believed industrial development and neighborhood density was taking a toll on the mental health of its citizens. In the mid to late 1800s, however, parks around Milwaukee were mostly held on private ground.

Often, citizens were charged a fee for access to enter. Even if the fee was small, it still restricted park usage for a segment of families. In addition to the lack of green space around the city, local politicians also voiced concern over the difficulty citizens had in accessing Lake Michigan’s beautiful lakefront.

At the time, only about 60 acres of scattered public land existed.

At the time, only about 60 acres of scattered public land existed. Seventeenth Ward Park (now Juneau) became the city’s first landscaped lakefront park in 1870. To further progress, the city formed the Milwaukee Parks Board in 1889. It was tasked to cultivate more land around the county as public park space.

The City’s First Parks Board

Milwaukee’s close proximity to Chicago would be the board’s first of two lucky breaks. In 1893, Architect Frederick Law Olmsted was working in Chicago on the World’s Columbian Exposition (also known as the Chicago World’s Fair). In the course of his career, Olmsted designed 100 public parks and recreation grounds, ranging from Central Park in New York City to the Emerald Necklace in Boston and Jackson Park in Chicago.

Olmsted’s vision was to provide parks for respite from the crowding and industrial despondency of urban America developing in the last half of the 19th century. He contended that municipal open spaces with scenic landscapes and recreational activities would promote both physical and mental health among its visitors from all walks of life. He believed it would also foster communication between social classes, thereby improving society.

Olmsted made himself available to help plan and design some of the city’s earliest parks. The board hired his firm to develop two of Milwaukee’s Emerald Necklace’s five original county grounds: Lake and River (now Riverside) Parks. Olmsted’s firm was later asked to design West (now Washington) Park. The look and feel of Olmsted’s original designs endure, if only in fragments, in each of his green spaces.

In addition to the county parks, Olmsted designed E Newberry Boulevard, connecting Lake and Riverside Parks. Completed in 1896, the board’s early park plans hoped to eventually include majestic boulevards as entryways and connections to all the city’s parks. Unfortunately, this feature has yet to come to fruition. Along with E Newberry Boulevard, only a handful exist.

Christian Wahl led the city’s first park board and was influential in hiring Olmsted. N Wahl Avenue makes up three blocks of Lake Park’s southwest border. The street was named for Wahl, who led advocacy to develop public parks when they were mostly private. The street is lined with mansions built in then popular German Renaissance styles, in contrast to American-styled architecture.

Milwaukee’s Emerald Necklace’s Oldest County Park

Work had already begun on the land along a northern bluff with a history stretching back to antiquity. Admired for its native forest and rolling topography, Lake Park was an obvious choice in the park commission’s early plans. In 1893, however, the park began to take the form of an Olmsted landscape.

Once having six natural ravines, one of the park’s openings was soon filled in to create a pastoral meadow. A path was created on the stretch of land along the bluff, winding through the park’s woodlands, ravines, and grasslands. Over the next few decades, the addition of the park’s key landmarks would be made.

Lake Park’s Five Bridges

Lake park is best known for the five bridges traversing its four remaining ravines. The design of four was credited to Oscar Sanne, a local engineer trained in Germany. His works include the well-known twin “Lion Bridges,” completed in 1897, guarding the North Point Lighthouse.

On the north end of the park, the brick arch bridge is the only one still open to vehicular traffic. Designed in a Renaissance Revival style, it crosses over the expansive north ravine. Just southwest, the steel arch footbridge gets its name from its six steel arches. Its two abutments—support walls on both ends—are made of limestone. This bridge stands near the dead end of N Lake Park Road.

The fifth bridge, known as Lake Park Bridge, ascends the now closed meandering Ravine Road. Originally built in 1905, it is a reinforced concrete deck arch bridge.

Credit for its design was given to the son of a German immigrant (and park’s commission member), Alfred Clas. Like Olmsted, his firm gained distinction during the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. Clas is also responsible for the blueprints of a number of mansions along N Wahl Avenue.

The Lake Park Bridge served the city for over a century before structural damage was discovered in 2014.

Cracks were found in the concrete and soil erosion was detected around the bridge supports. The restored bridge finally reopened in the fall of 2022. Ravine Road below, however, remains closed to traffic.

The Lion Bridges took a significant hit in 2014 as well. A 32,000 lb. semi-truck, hauling a 53-foot trailer, wedged itself behind the lighthouse into one of the twin bridges.

Claiming he did not see anything out of the ordinary in his chosen route, the driver’s GPS misadventure damaged multiple trees in addition to concrete railings on the two footbridges. They have since been repaired.

Presently, all five of Lake park’s original decorative bridges continue to enhance the natural features of the landscape.

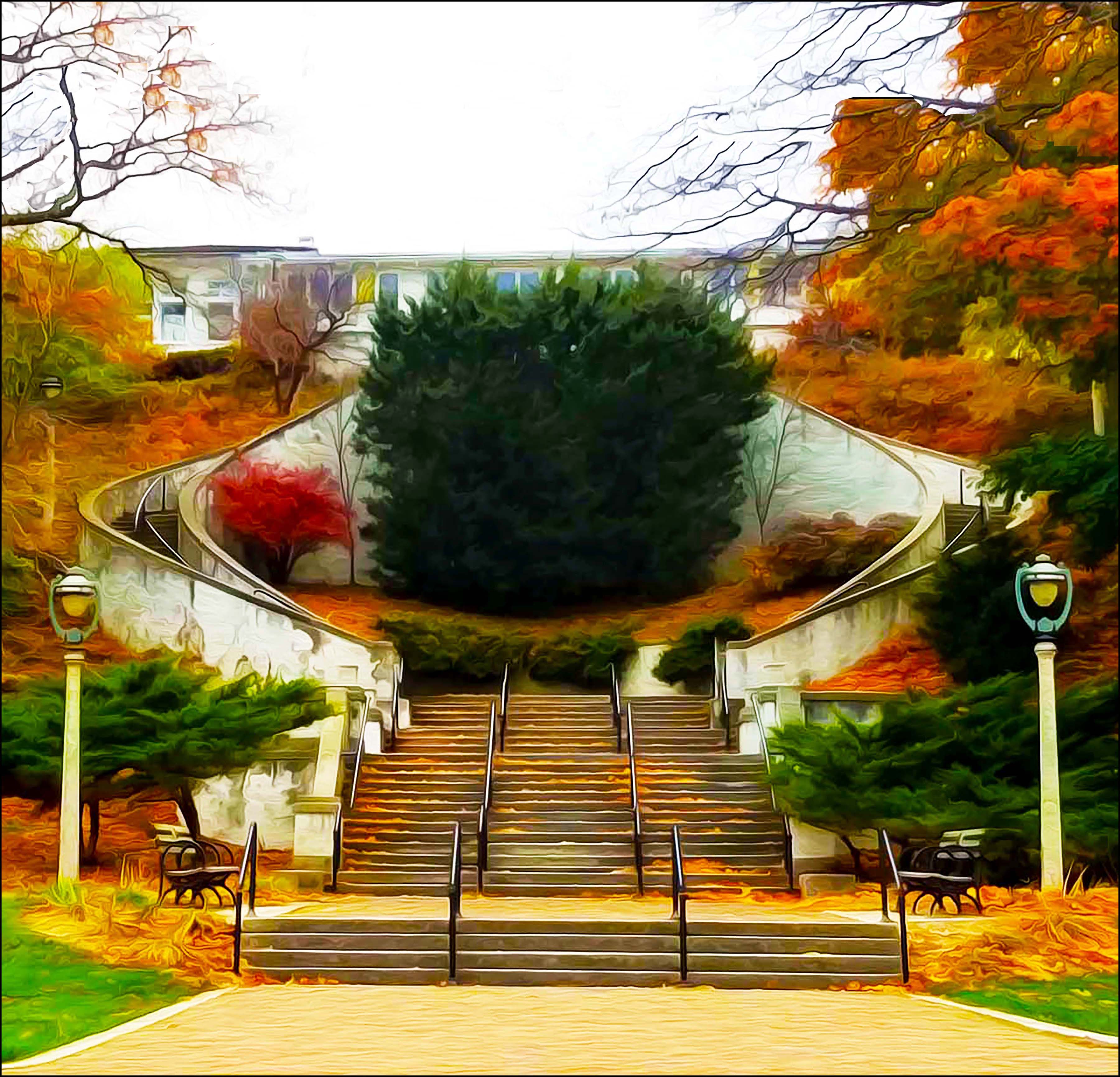

The Lake Park Pavilion & The Grand Staircase

Crossing to the south on the Lake Park Bridge leads you to the park’s pavilion, resting at the top of the Grand Staircase. The pavilion was dedicated in 1903, while the Grand Staircase was added in 1908. Both structures were also designed by the Ferry and Clas firm, who choose a neoclassical design. For nearly a century, the pavilion was used as a meeting place and a refreshment site.

Before there was a street along the shorelines, the Grand Staircase once descended from the back of the pavilion to a lakeshore walkway below. It also once connected to a promenade leading to an athletic field and spectator seating. The idea was to create a grand procession along the eastern edge of the park.

To this day, the stairway leads from the back of what is now the Bartolotta’s Lake Park Bistro, featuring upscale French fare, to the bottom of the bluff along N Lincoln Memorial Drive.

The North Point Lighthouse

The North Point Lighthouse marks the northernmost point of the Milwaukee Bay. The current lighthouse is in its third generation. Built along the bluff in 1855, the first was made of Cream City brick and topped with a cast iron mineral oil lantern.

The city is well-known for the uniquely colored Cream City brick, made from clay found along the Menomonee Valley’s river banks. It is naturally high in magnesium and lime, giving the brick its hue and durability. In the late 1880s, bluff erosion endangered the structure and plans for a replacement were drawn up. In 1888, a 40-foot cast-iron lighthouse tower was built 100 feet west. A lightkeeper’s quarters was also built alongside the structure.

Overtime, tree growth between the lake and tower obstructed its light. In 1912, the tower was dismantled and a riveted steel addition was erected at its foundation. The cream city brick tower was then placed on top, now reaching upwards 74 feet. The original 1855 lantern room was reused on the taller structure. The lantern was converted to coal gas until electrified in 1929.

In 1928, the keeper of North Point and the three keepers at the Milwaukee Pierhead Lighthouse—the small red lighthouse found at the end of the Summerfest grounds—were united. Until automation, all harbor lights were serviced by the resident lightkeepers stationed at the North Point Light Station.

The North Point Lighthouse was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1984. In 2003, Milwaukee County leased the lighthouse and keepers’ quarters to the North Point Lighthouse Friends, who began the restoration of both. The repaired landmark reopened as a maritime museum in 2007.

Together, these alluring park features formulate into a truly classic Olmstedian design. The Eastside’s Lake Park endures as one of the city’s oldest, most beloved, and well-cared for greenswards.

Eastside’s Riverside Park

Olmstead mapped out his next park around a natural ravine just to the west of Lake Park. River Park, now known as Riverside Park, was once a large gully sloping down from Oakland Avenue to the eastern banks of the Milwaukee River.

A carriageway was built from the top of the ravine down to its riverside. The wooded path was lined with ornate light fixtures to aid evening carriage travel.

The 15 acre park once included a sledding hill, a waterfall, and a park pavilion. The carriageway passed under the Chicago & North Western Railroad tracks through a large tunnel made of limestone blocks.

On the river, residents enjoyed swimming, fishing, boating, and winter ice skating. From there, the carriage road turned north, climbing back up and exiting at Locust Street.

Over the next 75 years, Riverside Park would go from a highly desirable destination to disrepair. Invasive plants took over the landscape while water pollution made the river unfit for swimming. As a result, the declining ravine park trail and its carriage tunnel were packed with landfill and flattened in the 1970s. Riverside High School’s athletic fields were then built along the railroad tracks and over the city’s historic trail.

By the 1990s, what was left of Riverside Park sat badly neglected. Covered with litter and graffiti, it became more known for its shady dealings. Community volunteers began organizing park cleanups in a revitalization effort.

Over time, nature and conservation classes were offered to residents from trailer homes parked on the site. This effort grew into The Urban Ecology Center (UEC), now a very popular urban nature center servicing the Milwaukee area. The UEC opened in 2004, providing nature walks and outdoor programming to families and students mostly living in heavily urbanized environments.

Meanwhile, the newly paved Oak Leaf Trail took the place of the old railroad tracks alongside the river. Riverside Park was transformed back into a magical green space. Although the stunning ravine trail is lost to history, decaying park features can still be spotted just underneath the graffiti and along the wooded trails.

The Mitchell Park Neighborhood

In addition to Lake and Riverside, three other public parks were part of the board’s earliest plans for Milwaukee’s Emerald Necklace: Coleman (now Kościuszko) Park, South (today’s Humboldt) Park, and Mitchell Park. West (today’s Washington) Park and North (now Sherman) Park were then added in 1891. Together, I call these the magnificent seven.

Mitchell Park, located on Milwaukee’s westside, overlooks the Menomonee Valley. it was built on land once owned by the prominent Mitchell family. Formally named Mitchell’s Grove, about 30 acres of land along the Menomonee bluff were used as the family’s private park until Alexander Mitchell’s death in 1887.

Already a thriving urban green space, 24.5 of those acres were purchased by the Commissioners for their grand park’s project. Five additional acres would later be donated by the Mitchell Family.

Work quickly began on the park’s first horticultural conservatory. The addition of Mitchell Park’s first horticultural conservatory was developed and constructed in 1898.

The glass-encased conservatory was inspired by London’s famed Crystal Palace. Just in front of the glass building was a sunken garden adorned with formal flower beds and a small pond.

Another English inspiration, the garden mimicked those of regal English homes. The original Mitchell Conservatory was used from 1898 to 1955.

Photo courtesy of Friends of the Domes.

In 1906, the Park Commissioners would secure yet another 28.5 acres from the John Burnham estate for Mitchell Park. Land purchased from the Milwaukee Southern Railway Company increased the size to a total of 62 acres.

Mitchell Park became a popular destination for boating and for free musical performances. Attended by huge crowds, concerts were often sponsored by the Milwaukee Electric Railway and Light Company operators. Their goal was to encourage patrons to use their street car services. During the winter months, children enjoyed ice skating on the frozen pond and sledding down the so-called “suicide hill” just south of the valley’s bluff.

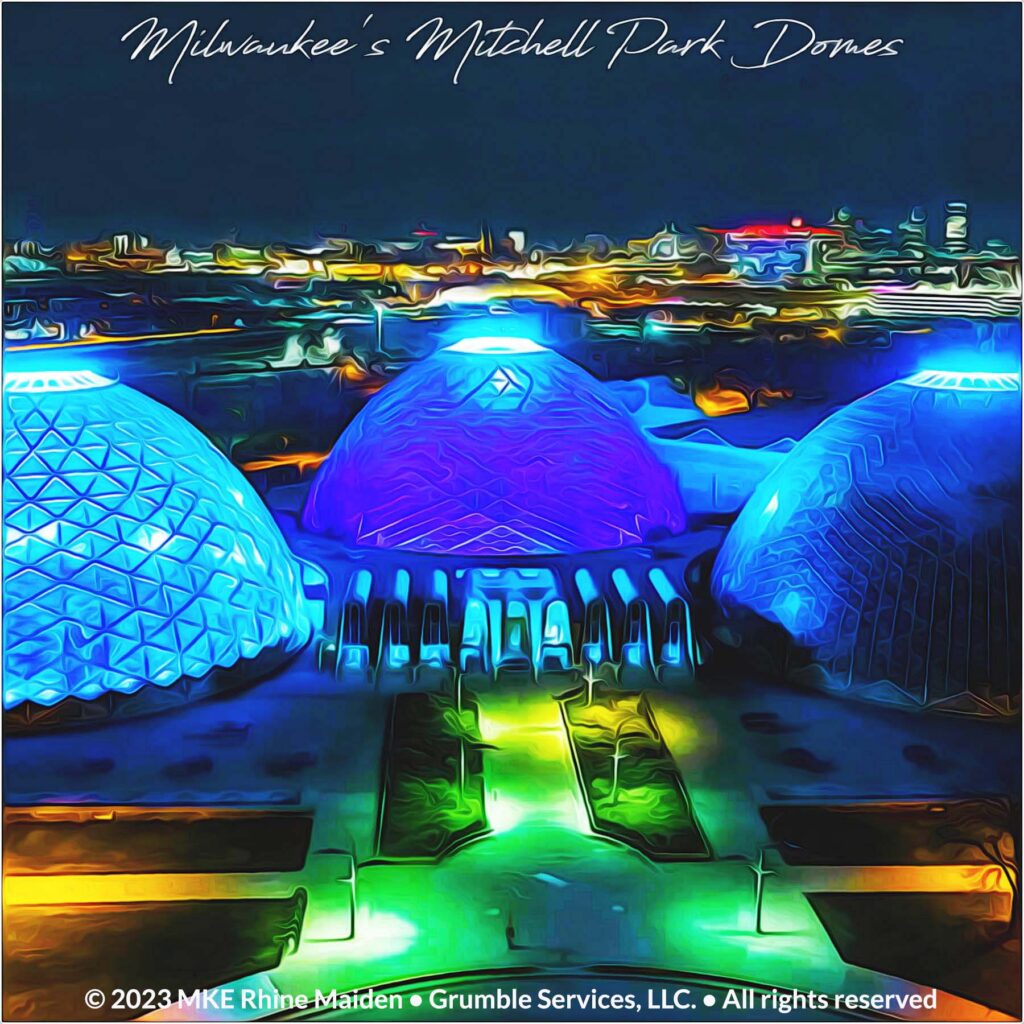

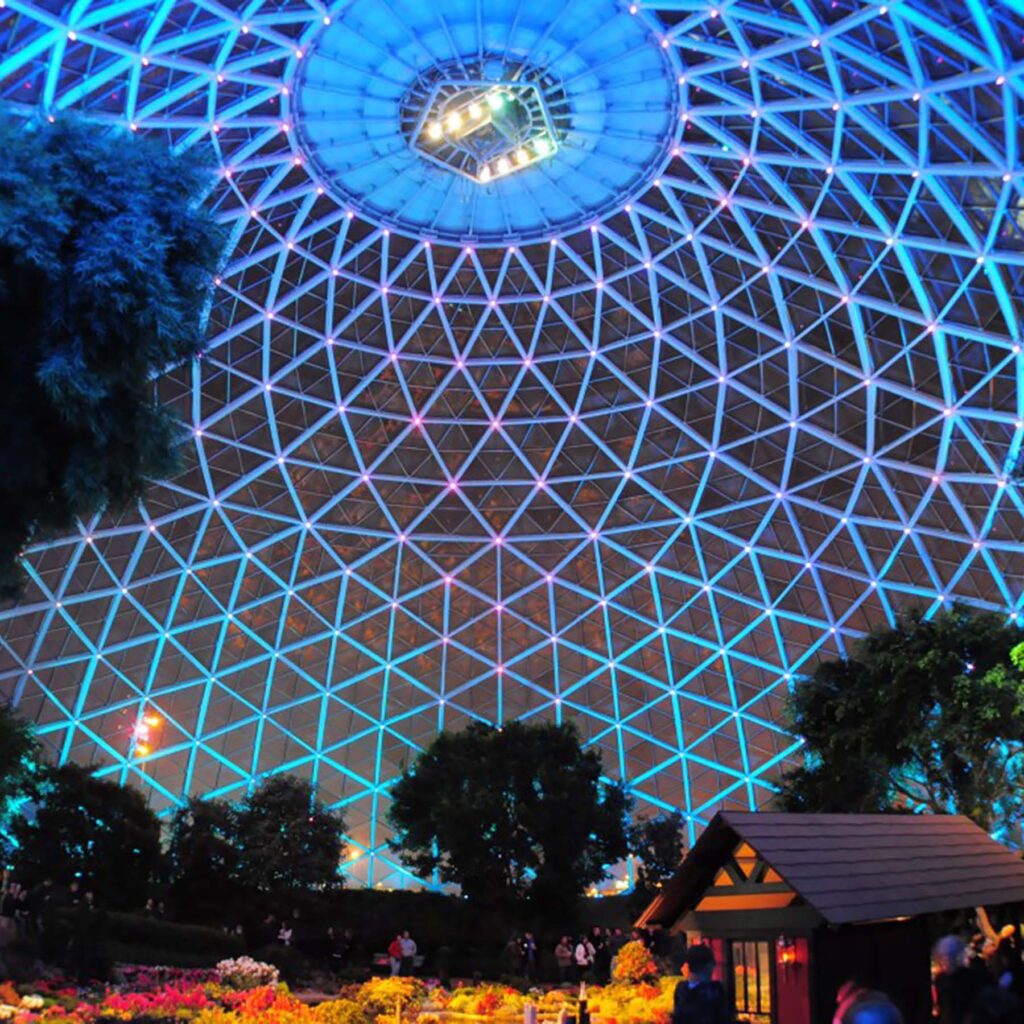

After six decades of patronage, the Milwaukee Conservatory was replaced with a new facility designed by local architect Donald L. Grieb. His design included three iconic, conoidal-paned domes, together covering an entire acre under glass. Each dome is 140 feet wide by 85 feet high, equating to seven stories!

First Lady Claudia “Lady Bird” Johnson dedicated the “show” dome in September of 1965. It features seasonal plants and special exhibitions. The tropical and arid domes then opened in 1966 and 1967. To this day, many consider these three domed structures to be the gem of Milwaukee’s public parks system.

Like so many other of the city’s parks, Mitchell Park has seen better days. Our world-class domes are in great need of repair. In 2016, steel mesh netting was put up to catch pieces of concrete falling away from the structure. With a bit of luck and forward thinking, city leaders will once again recognize this park’s rich historical value and give it the much needed attention it deserves.

Lincoln Village’s Kościuszko Park

The city purchased land in 1890 from a man named J.C. Coleman for the location of “Kosy” (pronounced “Kozzie”) Park, as known by locals. Originally named for Coleman, and for a time known as Lincoln Avenue Park, Kościuszko Park covers 33.5 acres on the southside of Milwaukee’s emerald necklace.

The park memorializes Polish General Thaddeus Andrzej Bonawentura Kościuszko (1746-1817). General Kościuszko fought on the American side of the Revolutionary War and in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth’s struggles against Russia and the Kingdom of Prussia. As Supreme Commander of the Polish National Armed Forces, he led the 1794 Kościuszko Uprising.

Early Milwaukee Polonia raised $13,000, collecting donations mostly ranging between 5¢ and 25¢ at a time, for the park’s most well-known feature: A bronze General Kościuszko on horseback with sword drawn in the air, readied for battle. Attended by 60,000 people, the statue was dedicated on June 18, 1905. Originally installed on the north side of the park, it was moved to its current location on its southside border near S 9th Place in 1951.

Over more than a century, patriotic celebrations, civil rights events, and other local happenings have been held in the shadow of the bronze Kościuszko. Kosy Park was once even the home of the Kościuszko Reds. The Reds were a franchise of the Polish-American Semi professional Baseball League until 1919.

Today, the park offers plenty of tree shade and open grass for a fun day outdoors. A large playground sits adjacent to its frequented community center and a three-acre fishing pond. The public space also provides neighbors a pool with waterslide and tennis courts.

Bounded by W Lincoln Avenue and S 7th Street to the southeast, Kosy sits kitty-corner to the early Milwaukee Polonia’s beloved Basilica of St. Josaphat. On sunny days, you can easily spot the large shadow cast by the neighboring basilica’s massive blue dome on the surface of the park’s pond.

St. Josaphat was born John Kuncevic about 1580 in Vladimir. This was a village of the Lithuanian Province of Volhynia, then a part of the Polish Kingdom begun under the Jagellonian Dynasty. In 1609, Josaphat was ordained a priest and began his career of preaching, spiritual direction and providing for the needy and homeless.

Inspired by St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, the Basilica of St. Josaphat was built in the style of Italian Renaissance. Using mostly recycled building materials from Chicago to save money, construction began in 1866. The church possesses an Italian style clock tower topped in the center with an imposing copper dome. The inside is not outdone by the outside. The European-style basilica possesses stunning interior paintwork.

To this day, it stands as the biggest church in Milwaukee County. St. Josaphat remains as a testament to the faith of the Polish immigrants who created it.

Bay View’s Humboldt Park

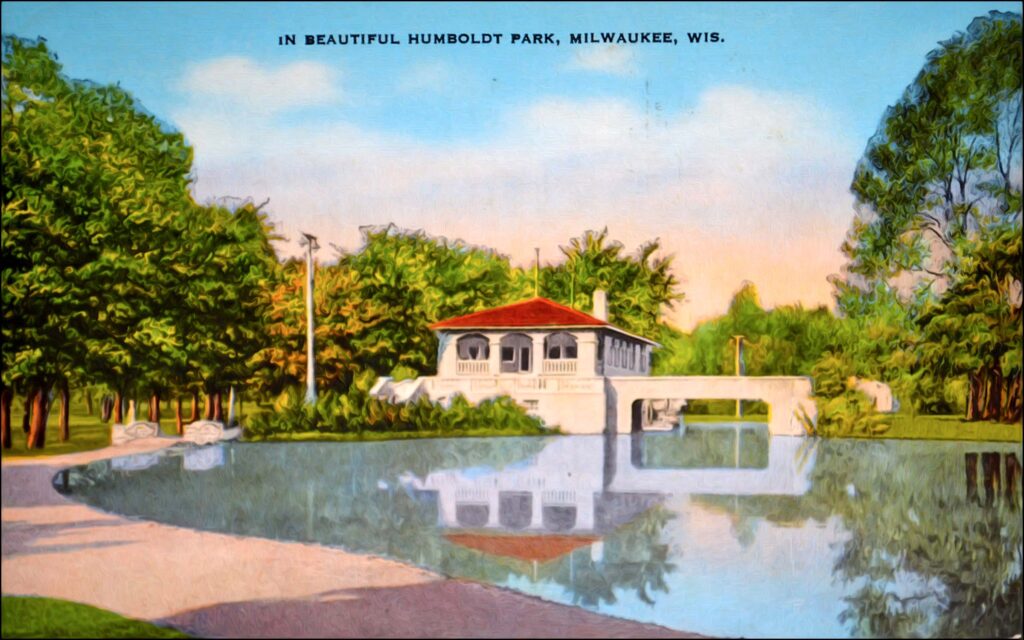

Like Kosy, the last of the five original parks also originates on the city’s southside. Originally named South, and for a time Howell Avenue Park, Humboldt Park covers 73 acres of the Bay View neighborhood. It was built over a fenced-in rolling tract of land once covered by woods along a rippling creek.

Its present name derives from the German naturalist, explorer, geographer, and “father of American environmentalism” Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859). Coincidentally, the popular colony of Humboldt penguins exhibited at the Milwaukee County Zoo’s front entrance for the past 35 years were also named for this famous explorer. These flightless, aquatic birds live on the shorelines of Peru and Chile where the chilly Humboldt Current runs along their natural habitat.

It is hard to imagine a boat house once standing along the lagoon’s southern shore.

It was built in 1893, along with a number of short bridges over its adjoining creek. A large, stone bridge then connected the boat house to the small island resting at the water’s center.

Both the bridge and boathouse were demolished in the 1950s, severing access to the water’s islet.

Photo courtesy of Humboldt Park Friends.

Once spanning from Howell to Logan Avenue, the park even provided horses with a drinking fountain near the center of its first paved street.

A monument made of Wisconsin red granite by the American Granite Company stands near the park’s lilly pond.

Paid for by donations raised by the Bay View Homecoming and Reconstruction Commission, it was constructed and dedicated in 1921.

Although not originally intended to be, it has been come to known as a memorial to Bay View’s 1,200 World War I veterans.

The New Deal allowed for the construction of two new landmarks during the 1930s: The park’s original Art Deco-style bandshell and the current farmhouse-style pavilion just west of the lagoon.

A grand staircase once ascended from the bandshell to the top of the tall hill near the center of the park. Regrettably, arson destroyed the original bandshell in 1975. In its place, the current Swiss chalet bandshell was built and dedicated in 1977.

A walk through Humboldt Park can be quite eventful on an average summer day. You might come across tennis lessons, cross country practice, a little league game, and children fishing at the lagoon or cooling in the splash pad.

On Tuesday nights, the Bay View Neighborhood Association provides Chill on the Hill on Humboldt’s outdoor music stage. “Are you going to Chill on Tuesday?” is a popular question asked among Bay Viewers. Alongside it, food trucks line the street while refreshments are enjoyed at the park’s beer and wine garden.

And, rest assured, you will also likely encounter the army of Geese often seen parading up and down the park’s central thoroughfare during your visit.

The Father of Milwaukee’s Emerald Necklace

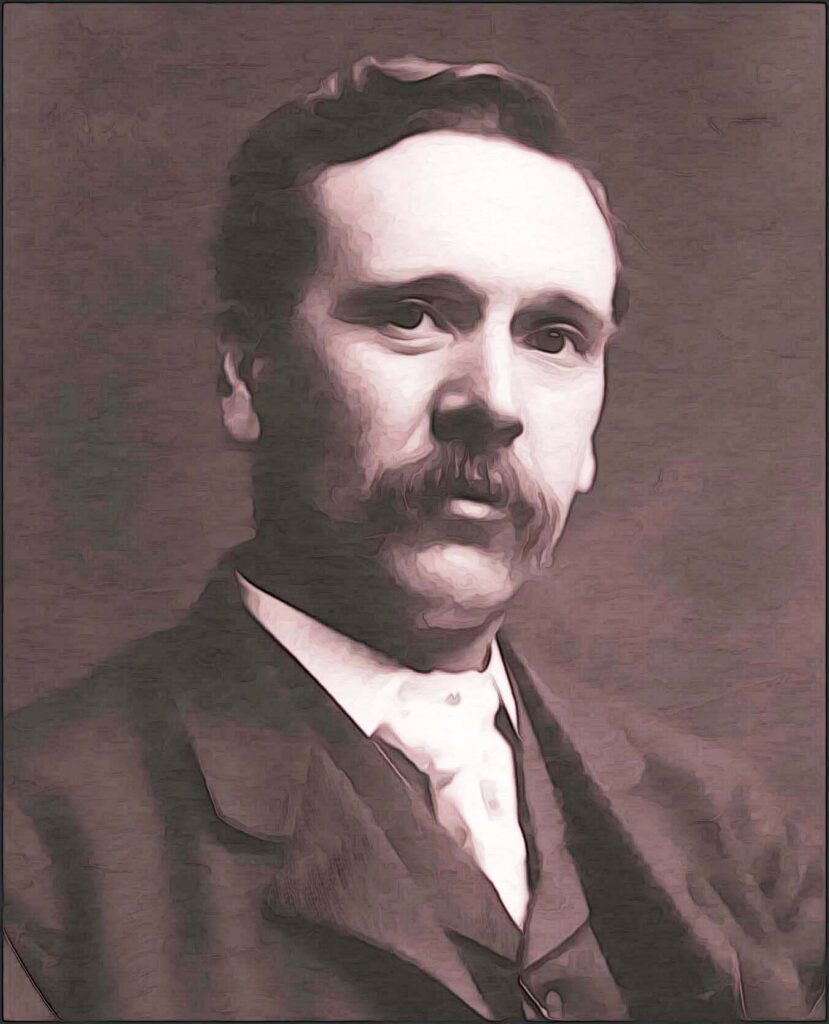

In order to extend out into rural areas around the city, the Milwaukee County Parks Commission was formed in 1907. The name best associated with it is Charles Whitnall (1859–1949). Under his influence, Milwaukee’s Emerald Necklace truly blossomed.

Charles Whitnall was both a key player in the creation of the commission and one of seven men appointed to it. His first land purchases outside the city proper included South Milwaukee’s County (now Grant) Park and Wauwatosa’s Scholes (now Jacobus) park.

Becoming the city’s first socialist city treasurer in 1910, Charles Whitnall shared a similar vision with Milwaukee’s Sewer Socialists. Whitnall intermixed his political desires to aid Milwaukee’s urban poor while protecting undeveloped county green spaces.

Where unspoiled rivers, rolling hills, and woodlands could be found, he saw great possibility. Master plans were drawn up for Milwaukee’s Emerald Necklace in 1923. The result would be a wide-ranging municipal park system encircling the city.

Image courtesy of the Milwaukee County Historical Society.

The commission’s second of two lucky breaks came in the form of the American New Deal, a series of programs and projects created during the Great Depression. President Franklin D. Roosevelt aimed to restore prosperity to Americans by providing jobs and relief as quickly as possible to those struggling. The regulations were enacted between 1933 and 1939. Because the county’s park plans were already completed, the Commission quickly secured federal relief funds and put Whitnall’s long-term plans into action.

Once the New Deal was launched, The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and The Works Progress Administration (WPA) were both established, employing millions of job seekers to carry out public work projects. Throughout the Mid–1930s, young men completed miles of physical construction on bridges, parkways, bathhouses, pavilions, shelters, and swimming pools. Milwaukee’s Emerald Necklace truly began to take form.

Milwaukee County’s Parks Today

Today, as a result of Charles Whitnall’s 1923 master plan, Milwaukee’s Emerald Necklace remains largely intact. His plan proved to be decades ahead of its time. The city’s long tradition of preserving land for public use has accumulated into nearly 15,000 acres of green space and 169 parks, 140 miles of trails, 15 golf courses, and hundreds of play areas, picnic sites, and athletic fields.

The Fate of Milwaukee’s Emerald Necklace

By 1981, budget cutbacks resulted in the elimination of the County Park Commission. A new county department was created to take its place, but the funding cuts led to layoffs, demand maintenance, and site closures such as Milwaukee’s Emerald Necklace‘s beloved Sunken Gardens in Mitchell Park.

On a more positive note, European Biergartens have made a comeback in recent decades. The county currently offers five permanent and two traveling beer gardens. Sadly, they have now become the park system’s most critical source of funding. So, please visit them often and buy lots of the beer Milwaukee made famous!

Here I’ve only highlighted five of Milwaukee’s Emerald Necklace‘s parks. There’s so much out there just waiting to be learned. The best part? A walk in any park designed for the emerald necklace is free. The possibilities are endless!

Milwaukee’s Emerald Necklace. Send comments and feedback to MKERhineMaiden@gmail.com.

© 2024 MKE Rhine Maiden • Grumble Services, LLC. • All rights reserved.

Photos & illustrations are by the author unless otherwise noted.

References and Read More:

Making of Milwaukee (Parts 1, 2, 3). John Gurda. Milwaukee PBS, 2006.

Muench Albano, Laurie (2007). Milwaukee County Parks (WI) (Images of America). Arcadia Publishing, Charleston SC.

Swanson, Carl (2018). Lost Milwaukee. The History Press, Charleston SC

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee (2016). https://emke.uwm.edu. Accessed April 1, 2024.

Why is walking so good for the brain? Blame it on the “spontaneous fluctuations”

By Thomas Nail (August, 2021)